There and back again – A student’s linguistic landscape adventure in Basel’s museums – by Dogan Coban

Art/Music

Small. This adjective certainly applies to Basel. Dense. This one, without doubt, does too. This density shows in the plethora of different museums all around the city. One of the (one might add here internationally) more renown ones is the Kunstmuseum in the heart of the city. Another one, much less known (one might add here locally) is the Antikenmuseum, 1 minute away. The clienteles of the former are much more likely to not speak German. Whereas for the latter one, the clienteles are locally grown German speaking people. Of this fact, it seems, both museums are aware, and this awareness is reflected in the linguistic landscape of the two.

English, as the global Lingua Franca, is present in both museums, but its frequency and dominance varies considerably. This variation is shown for example in the cloakrooms. In the Antikenmuseum’s cloakroom there was no English to be found. No instructions, no disclaimers, nothing. It seems that English speaking visitors will be utterly lost as to where and how to hang their cloaks. The Kunstmuseum is much more caring of their international visitors as there are clear and visible instructions not only in English and German but also in French. Though, as the pattern of English (and French) use in the linguistic landscape of the Kunstmuseum will show, a lack of a precise concept seems apparent. German dominates in this cloakroom though, followed by English and French, again in this order, as some instructions are only bi- and some only monolingual. Thus, compared to the Antikenmuseum, the Kunstmuseum actually expects English speaking visitors and wants their clothes to be safe.

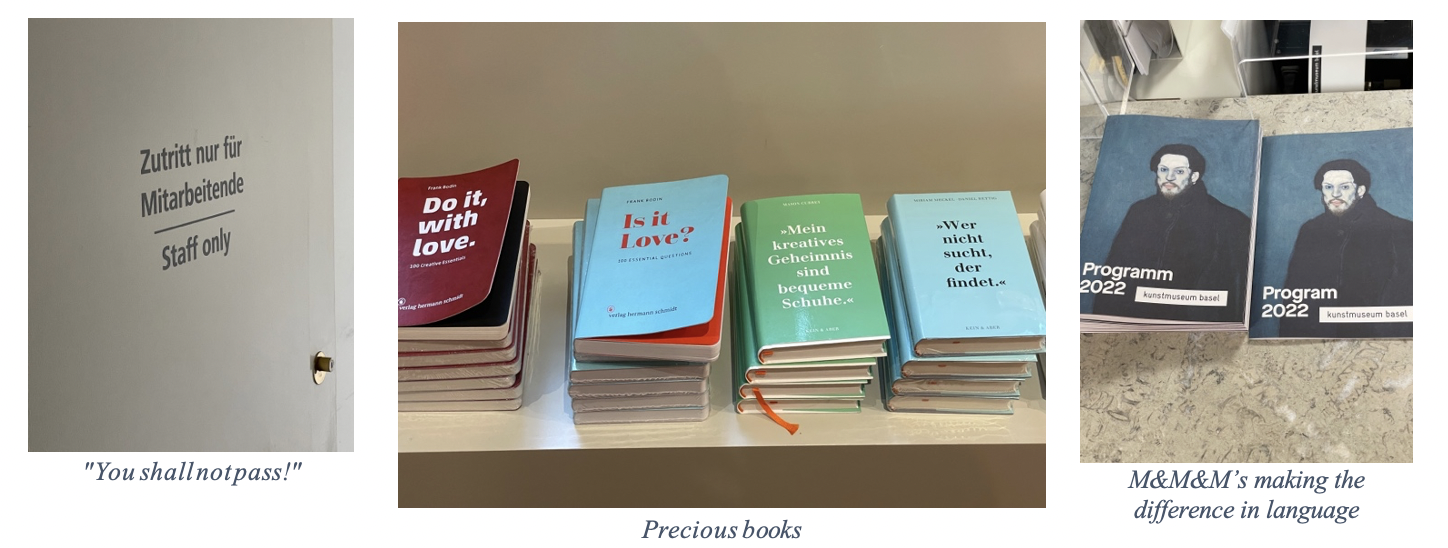

Both museums also included little bistros for their visitors. In the Antikenmuseum’s bistro, hungry visitors are instructed by a sign to wait before being seated by the staff. Other than that, the only use of English is at a wall separating the public space from “Staff only” spaces.

Everything behind that wall is written in German. Not a lot of English usage here then and no French at all. The bistro in the Kunstmuseum does not fare better in this regard: next to a “welcome” and “enjoy” the only English present is in Corona hygiene and safety instructions. Food is also a Lingua Franca it seems.

The situation in the other room – after which’s visit one might find ones wallet lighter – the shops, is quite different. While in the Antikenmuseum, where only postcards are sold, the appearance of English is limited to the rather stingy phrase “Please only touch objects if you intend to buy”, the case in the shop of the Kunstmuseum is quite different and confusing. The landscape of the books presented there is a wild mishmash of exclusive English covers, exclusive German books, different editions of the same book in German and in English placed next to each other, German books with English titles, and DVDs in both languages. Not only books and DVDs are sold in the souvenir shop though, but also writing and drawing utensils like pencils, sketchbooks, etc. Confusingly, the product descriptions are either monolingual (German or English) or bilingual (German and English); the reason for this is lost to me. The signs for product categories are mostly presented in German, with the occasional cheeky anglicism here and there. French speakers are probably expected to shop online.

To try to find a conclusion in this linguistic landscape adventure through two of my favorite museums in Basel, and this is not only due to us getting a free ticket in, public exhibitions are sometimes more and sometimes less adjusted to English speaking visitors. The targeted demographics vary considerably on the specific museums niche. The Antikenmuseum seems to target local German speaking visitors as English is not a primary focus in their linguistic landscape. However, English and other language speakers will probably not get lost in the small museum. Whereas the Kunstmuseum, which expects, next to local visitors, a significant number of international art-enthusiasts and tourists, very deliberately works with English in their linguistic landscape. Even though, again but for another reason, I doubt that any English speakers will get lost in the Kunstmuseum, I cannot grasp their concept by any means. Fortunately, for all visitors of museums in general the exhibited objects speak for themselves.

By Dogan Coban